Yaqing Hou, Wenqiang Ma, Abhishek Gupta, Kavitesh Kumar Bali, Hongwei Ge, Qiang Zhang, Carlos A. Coello Coello Fellow, IEEE and Yew-Soon Ong, Fellow, IEEE

In particular, transfer evolutionary optimization (TrEO) has emerged as a computational intelligence paradigm that facilitates knowledge transfer in evolutionary computation from previously solved source tasks to address a new target task of interest [1]. In recent years, numerous TrEO algorithms have showcased their efficacy across various domains, emphasizing the potential for specialization in evolutionary optimization [2,3]. Despite these advancements, the recently proven "no free lunch theorem" (NFLT) in transfer optimization [4] highlights a critical observation - no single algorithm universally outperforms others across perse problem types. A comprehensive literature review, exemplified by studies like [4], substantiates the NFLT's validity, revealing no algorithm's supremacy over others across numerous synthetic problems. This phenomenon is conjectured to become even more apparent in practical scenarios, where a multitude of generated source tasks often exhibit higher persity and complexity.

Existing TrEO studies often focus on empirical analyses of optimization performance using synthetic benchmark functions in idealized settings [5-7]. Many of these functions are perceived as disconnected from reality. A recent paper has offered proof of faster convergence through transfer in the surrogate-assisted optimization setting [8]. However, aside from a handful of such work, the general shortage of formal results offering performance guarantees for TrEO, coupled with the need for better evaluation and benchmarking[4], poses challenges in understanding how the proposed algorithms would perform in real applications. Without appropriate benchmark problems, a comprehensive assessment of TrEO's efficacy in coping with the implications of the NFLT in real-world situations is difficult.

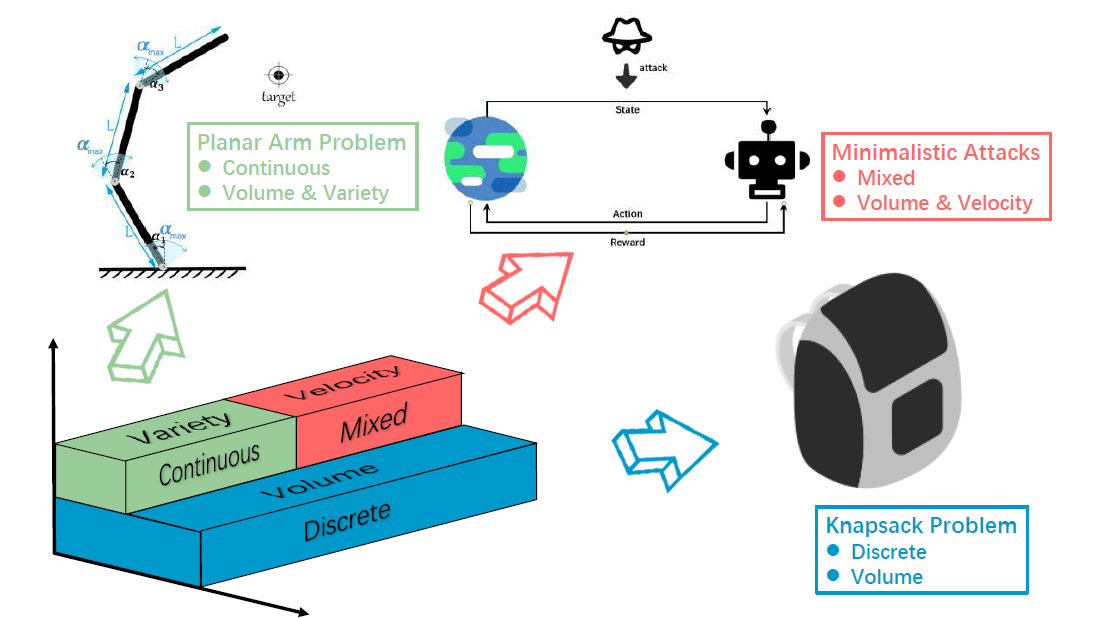

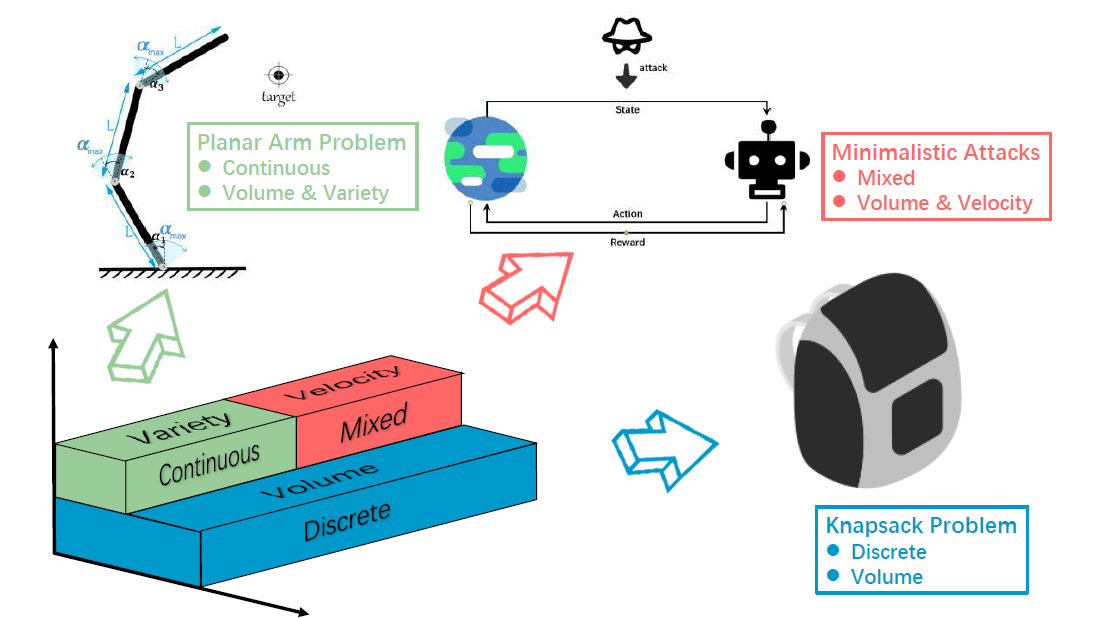

To address this limitation, this paper adopts a benchmarking approach to evaluate the performance of several TrEO algorithms in realistic scenarios. Our objective is to gain a deeper understanding of algorithmic performance when confronted with perse and complex transfer scenarios, each possessing its unique strengths and weaknesses. The paper pioneers a practical TrEO benchmark suite, integrating problems from the literature categorized based on three postulated V's of Big Source Task-Instances: Big Volume (given a static but substantial number of source tasks), Big Variety (under a wide range of source tasks with varying elements of optimization problems), and Big Velocity (for efficient transfer optimization in time-sensitive environments). By introducing realistic benchmarks embodying the three dimensions of volume, variety, and velocity, we aim to provide a comprehensive analysis of existing TrEO algorithms and foster a deeper understanding of algorithmic performance in the face of perse and complex transfer scenarios.

The rise of Big Source Task-Instances and the increasing number of potentially similar historical source tasks pose challenges in efficiently reusing knowledge for TrEO. We investigate three fundamental characteristics of TrEO problems related to Big Volume, Big Variety, and Big Velocity, which shape the performance and effectiveness of TrEO algorithms in real-world problem-solving scenarios. These characteristics play a crucial role in determining the scalability, adaptability, and efficiency of TrEO algorithms in handling large and perse source tasks, as well as in addressing transient and rapidly changing optimization landscapes. By categorizing our benchmarking test suite based on these characteristics, we aim to provide a comprehensive evaluation of TrEO algorithms' capabilities and limitations across different problem domains and complexities.

Definition 1:

A Big Volume of Source Task-Instances: a static but substantial number of previously solved source tasks.

The masses of source tasks could contain potentially useful knowledge for optimizing a target task. TrEO with a big volume of source task instances poses several challenges in practical optimization scenarios. One major challenge is the increased computational cost required to handle large volumes of source data [9]. Furthermore, the transfer of knowledge from a multitude of related problems becomes more difficult, and the risk of negative transfer increases. Identifying relevant and transferable knowledge among the large pool of source tasks becomes a critical task [10].The issue is compounded when a significant proportion of the source tasks are not relevant to the target optimization task. This necessitates the development of specialized techniques and the use of powerful computational resources to effectively tackle the challenges posed by big volumes of source tasks. For instance, in the large-scale cloud-based platforms of today, online services catering to thousandsof perse clients worldwide have emerged. Locating the relevant source priors among these large volumes of ``pre-solved'' cases could have a significant impact on enhancing service efficiency as well as the quality of solutions recommended to any new target client.

Definition 2:

A Big Variety of Source Task-Instances: a large range of source tasks with different elements of optimization problems, including differing dimensionalities and solution representation of variables, heterogeneity of the search space, differing objectives and constraints, etc.

In a significant body of TrEO studies, researchers often assumed the configuration of identical optimization elements across source and target tasks [11]. Therefore, the well-optimized knowledge extracted from source tasks can positively direct the search process of target tasks. In real-world scenarios, the mismatch in optimization elements between source and target tasks often occurs. However, this does not necessarily imply that the unrelatedness across tasks and their true relationship may be concealed.This necessitates finding appropriate transformations or mappings of search spaces between mismatched optimization elements to increase the overlap in solution distributions and uncover latent similarities or connections between tasks [12].To illustrate this, consider the example of a planar robotic arm task, where the goal is to reach a pre-specified point with a robotic arm possessing specific characteristics. In this scenario, the source tasks may exhibit variations in optimization elements, such as dimensionalities and robot arm length, leading to differences in variable and objective features. Consequently, knowledge derived from source tasks needs to undergo a mapping or a transformation before it can be effectively utilized, as the variations in the optimization elements create different domains for each task. Therefore, addressing the wide variety of source task-instances demands the development of transfer optimization methods that can adapt to transfer between tasks with perse optimization elements by mapping or transforming knowledge from different domains for efficient knowledge transfer.

Definition 3:

A Big Velocity of Source Task-Instances: the high speed of optimizing target problems towards a certain level of fitness performance (often by leveraging knowledge from a considerable number of source tasks) given limited time and computational power.

It is a requirement for efficient transfer optimization in time-sensitive environments and poses a significant challenge in practical transfer optimization problems. As the size of the source data increases, the algorithm's analysis time also grows. In many real-world optimization scenarios, the need to find an optimal solution within the shortest possible time is crucial [13]. Furthermore, some practical problems demand algorithms to achieve satisfactory objective values within strict time constraints as well [14]. For instance, consider the context of attacking a pre-trained policy in a sequential decision-making setting, where the optimization algorithm must add perturbations to an agent's observations to deceive it into altering its actions. Such attacks can be seen as a form of defense against an offensive adversary. Here, time is limited, and the algorithm must launch a successful attack within a tight time window before the key frame vanishes. In such contexts, time efficiency becomes a critical consideration alongside data efficiency. The focus shifts towards algorithms that can efficiently leverage prior knowledge and past experiences to converge rapidly towards high-quality solutions within a shorter timeframe [9]. The ability to adapt and transfer knowledge effectively is crucial for prompting decision-making and achieving near-optimal solutions.Addressing the challenge of big velocity in source task-instances necessitates the development of agile and time-efficient transfer optimization algorithms. Techniques that capitalize on the temporal context of the target task and leverage sophisticated transfer learning strategies can enable algorithms to make swift and informed decisions. Integration of real-time optimization methodologies and online learning approaches can further enhance the time efficiency of transfer optimization algorithms.

Having thoroughly examined the characteristics discussed in the preceding sections, we propose a problem test suite comprising three practical optimization problems. Each problem is selected to represent distinct facets of complexity and persity commonly encountered in real-life applications. The knapsack problem is a classical combinatorial (discrete) challenge with a focus on Big Volume of previously solved source tasks. The planar arm problem represents a continuous optimization scenario, characterized by both Big Volume and Big Variety of source tasks. Minimalistic attacks encompass mixed optimization problems that exhibit characteristics of Big Volume and Big Velocity. The properties of the aforementioned problems can be summarized as follows:

[Our code can be downloaded via here]

README:

As described in the paper, there are three different problems, i.e. 0/1 knapsack problems, planar arm problems, and minimalistic attack problems. their sources tasks are stored in the following folders, respectively.

Note that only source problems definitions are exited in above folders, u need use simple optimization algorithms to get respective candidate solutions or models. Meanwhile, we offer methods to load and optimize those source tasks. The basic solver is GA, if u need use other optimizers, just fix the codes.

U can run enjoy_benchmark_[knapsack|arm|attack] to enjoy our benchmark. If u want to use a optimizer rather than GA, u can use load_[knapsack|arm|attack]_sources to load source tasks and get_[knapsack|arm|attack]_fitness_function to get predefined fitness function.

Python 3.6 is used in our experiments, the protocols of pickle is different if your python version >= 3.8. Thus u can not load pickle files we prepared. To use our benchmark, u need install the python package stable_baselines, u can refer to [Stable_Baselines-User_Wizard-Installation].

Yaqing Hou, Wenqiang Ma, Hongwei Ge, and Qiang Zhang are with the School of Computer Science and Technology, Dalian University of Technology (DLUT), China 116024 (E-mails: houyq@dlut.edu.cn; ranyi@mail.dlut.edu.cn; gehw@dlut.edu.cn; zhangq@dlut.edu.cn).

Abhishek Gupta is with the School of Mechanical Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Goa, India (E-mail: abhi.nitr2010@gmail.com).

Kavitesh Kumar Bali is with the Centre for Frontier AI Research (CFAR), Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*star), Singapore (E-mail: bali.kavitesh@gmail.com).

Carlos A. Coello Coello is with the Departamento de Computación, CINVESTAV-IPN, Mexico City, Mexico. This work is part of his sabbatical leave at the Basque Center for Applied Mathematics (BCAM) \& Ikerbasque, Spain (e-mail: carlos.coellocoello@cinvestav.mx).

Yew-Soon Ong is the Chief Artificial Intelligence Scientist with the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), Singapore, and is also with the Data Science and Artificial Intelligence Research Centre, School of Computer Science and Engineering, Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore (email: asysong@ntu.edu.sg).

[1] A. Gupta, Y.-S. Ong, and L. Feng, “Insights on transfer optimization:

Because experience is the best teacher,” IEEE Transactions on Emerging

Topics in Computational Intelligence, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 51–64, 2017.

[2] T. Wei, S. Wang, J. Zhong, D. Liu, and J. Zhang, “A review on evolution-

ary multitask optimization: Trends and challenges,” IEEE Transactions

on Evolutionary Computation, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 941–960, 2021.

[3] A. Gupta, L. Zhou, Y.-S. Ong, Z. Chen, and Y. Hou, “Half a dozen

real-world applications of evolutionary multitasking, and more,” IEEE

Computational Intelligence Magazine, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 49–66, 2022.

[4] E. O. Scott and K. A. De Jong, “First complexity results for evolu-

tionary knowledge transfer,” in Proceedings of the 17th ACM/SIGEVO

Conference on Foundations of Genetic Algorithms, 2023, pp. 140–151.

[5] B. Da, Y.-S. Ong, L. Feng, A. K. Qin, A. Gupta, Z. Zhu, C.-K. Ting,

K. Tang, and X. Yao, “Evolutionary multitasking for single-objective

continuous optimization: Benchmark problems, performance metric, and

baseline results,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.03470, 2017.

[6] Y. Yuan, Y.-S. Ong, L. Feng, A. K. Qin, A. Gupta, B. Da, Q. Zhang,

K. C. Tan, Y. Jin, and H. Ishibuchi, “Evolutionary multitasking for mul-

tiobjective continuous optimization: Benchmark problems, performance

metrics and baseline results,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.02766, 2017.

[7] A. Viktorin, R. Senkerik, M. Pluhacek, T. Kadavy, and A. Zamuda,

“Dish-xx solving cec2020 single objective bound constrained numerical

ptimization benchmark,” in 2020 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary

Computation (CEC), 2020, pp. 1–8.

[8] J. Liu, A. Gupta, C. Ooi, and Y.-S. Ong, “Extremo: Transfer evolutionary

multiobjective optimization with proof of faster convergence,” IEEE

Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, pp. 1–1, 2024.

[9] M. Shakeri, A. Gupta, Y.-S. Ong, X. Chi, and A. Z. NengSheng, “Coping

with big data in transfer optimization,” in 2019 IEEE International

Conference on Big Data (Big Data). IEEE, 2019, pp. 3925–3932.

[10] M. Shakeri, E. Miahi, A. Gupta, and Y. Ong, “Scalable transfer evolu-

tionary optimization: Coping with big task instances,” IEEE transactions

on cybernetics, vol. PP, 2022.

[11] R. Lim, A. Gupta, Y.-S. Ong, L. Feng, and A. N. Zhang, “Non-linear

domain adaptation in transfer evolutionary optimization,” Cognitive

Computation, vol. 13, pp. 290–307, 2021.

[12] R. Lim, L. Zhou, A. Gupta, Y.-S. Ong, and A. N. Zhang, “Solution repre-

sentation learning in multi-objective transfer evolutionary optimization,”

IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 41 844–41 860, 2021.

[13] G. Sanchita and D. Anindita, “Evolutionary algorithm based techniques

to handle big data,” Techniques and Environments for Big Data Analysis:

Parallel, Cloud, and Grid Computing, pp. 113–158, 2016.

[14] M. Diehl, H. G. Bock, J. P. Schl ̈oder, R. Findeisen, Z. Nagy, and

F. Allg ̈ower, “Real-time optimization and nonlinear model predictive

control of processes governed by differential-algebraic equations,” Jour-

nal of Process Control, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 577–585, 2002.